“Life and death went hand in hand; wealth and poverty stood side by side; repletion and starvation laid them down together. But it was London.” —Charles Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby (1839)

This chapter functions as an extension of the Cthulhu by Gaslight: Investigators’ Guide; it provides further historical background, particularly for those aspects of society that are not known to the public at large—more detail on institutions only accessed by the penniless and destitute; on prisons; on asylums; and on crimes of the Gaslight era. There’s also a selection of useful floorplans and villainous organizations.

In addition, within are details about the rule of law, and the criminal underworld. Fair warning: Victorian society was rife with exclusion, discrimination, and oppression based on class, gender, sexuality, and race—though not always along the lines modern readers may expect—as well as new and unexpected opportunities for the fortunate.

Desperate Measures

The “Poor Laws” of the 18th and 19th centuries placed the responsibility of caring for the destitute on local parishes. Applicants could only apply for public assistance to the parish of their permanent residence. This could be in the form of “outdoor relief,” i.e., financial or material assistance given to people in their own homes, or on the street.

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 largely abolished outdoor relief and made it so that anyone requiring assistance had to enter a workhouse instead and submit to a regime of forced labour. It was an egregious, regressive piece of legislation designed primarily to reduce this burden of public assistance upon local taxpayers. Its explicit purpose was to make falling back on public welfare so awful that the poor would do literally anything else instead, the assumption being that poverty was a lifestyle choice. The “Bastardy Clause” also absolved the father of any illegitimate child of all financial responsibility, putting the entire burden on the mother.

- 1834: Poor Law Amendment Act—the creation of workhouses.

- 1872: Infant Life Protection Act—requires foster carers to register with the parish.

- 1897: Infant Life Protection Act—allows local authorities to regulate child carers.

The Workhouse

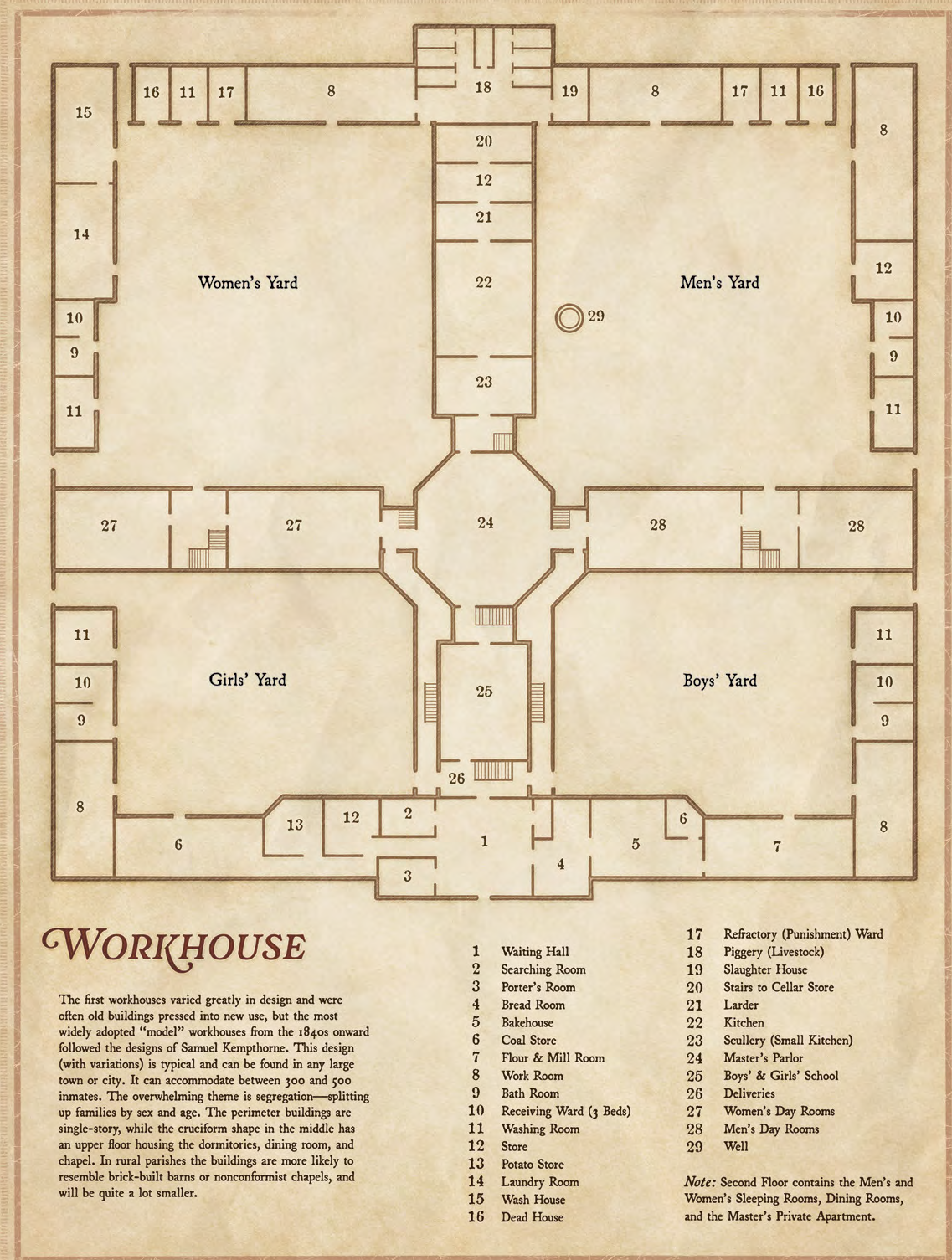

As the 19th century progressed, different parishes “clubbed together” in response to the needs of the rising population to form poor law unions and construct workhouses capable of caring for the poor of dozens of parishes. An annually elected Board of Guardians, all wealthy taxpayers, runs each workhouse. After 1871, oversight of the workhouse system goes to the Local Government Board, whose president is a government Cabinet Minister.

The prospect of the workhouse instils utter fear and shame in the working classes, especially as they grow older—though unemployment, illness, and disease can also drive people there. It is not an exaggeration to state that many people literally starve to death instead of submitting to the workhouse. It is not simply the horrible physical conditions, but the humiliation, the loss of autonomy, and the separation from family that amounts to a surrender of the sense of self. Entry to a workhouse is voluntary for adults, and “inmates” can, in theory, leave with a few hours’ notice—although they must pay off the previous day’s relief with work, married men may not leave their wives behind, and parents must take their children with them to prevent the dumping of unwanted offspring on the parish. As well as adults, abandoned children and orphans can end up in the workhouse as a means to care for them, though in the late-Victorian era there are an estimated 30,000 orphaned or abandoned children living on Britain’s streets. Leaving while still in workhouse uniform results in a charge of theft and, until 1911, married women cannot leave the workhouse without permission from their husband.

The workhouse doors are always locked, but open at 6:00 pm each evening for those hoping for a bed in a “casual ward,” which is separate to the rest of the establishment. At facilities with limited capacity, applicants may begin queuing much earlier. The casual wards house the vagrants and “destitute wanderers,” such as construction workers or laborers (“Navvies”) walking between jobs. In return for a morning’s work, the recipient gets a bath, a bag of straw to sleep on in a common room (though workhouses built after 1870 introduce individual cells that lock from the outside), supper, and breakfast. Staff temporarily confiscate any tobacco, money, and alcohol, and segregate the sexes. From 1882, those entering a casual ward must stay for two nights, with a full day’s work between. Applicants may not return to the same casual ward for 30 days.

The relieving officer conducts interviews with those who wish to enter the workhouse indefinitely, and issues a certificate (“chitty”) permitting this. To qualify for permanent workhouse residence, a person must belong to the parish—for men, this usually means having lived and worked there for a year; women and children qualify based on the husband/father’s “right of settlement.” Most workhouses require married men to bring their dependents with them, and they might turn away a woman if she has family that could notionally provide for her, especially if she admits to being married. Upon entry into the workhouse proper, the staff sort inmates into the following categories:

- Men infirm through age or illness.

- Women infirm through age or illness.

- Able-bodied men aged 15-60 years.

- Able-bodied women aged 15-60 years.

- Boys aged between 7 and 14.

- Girls aged between 7 and 14.

- Children under the age of 7.

Each person receives a bath, a medical examination, and a “workhouse dress” (which resembles a uniform)—workhouse staff store away personal clothing and possessions in case the inmate should choose to leave. They separate the families, except for children under the age of two, sometimes never to see each other again, as each category is allocated to a communal dormitory, with segregated dining and work areas. It is this separation that most frightens inmates. Desperate overcrowding exists in all areas and facilities, and architects set the windows and walls to prevent any view of the outside world.

The master, who lives on site, is in overall control of the workhouse and its staff; the matron (usually his wife) oversees the women and children under seven years.

To earn their rations (which law dictates must be worse than those of the local poor) inmates must clean, cook, break rocks for road-making, pick the pitch from old ropes by hand to make oakum fibre, or smash bones to make fertilizer. Law dictates that children must study their letters and numbers for three hours a day, along with marketable skills to help them find work. Staff sequester the sick to the infirmary, and while the elderly must work, they sometimes receive slightly easier tasks such as sack-making or cleaning—but such conditions depend on the master of the house and the institution in question, as not all are “forward” thinking and there is, of course, abuse and corruption. Explorer Henry Morton Stanley was a workhouse child who, in his autobiography, described it as a “house of torture.” By his own account, he ran away to sea after beating up a staff member who whipped and abused a friend to death.

A typical day in a workhouse consists of breakfast at 6:30 am, followed by work from 7:00 am to 12:00 pm, a lunch from 12:00 pm to 1:00 pm, then more work between 1:00 pm and 6:00 pm, with dinner served at 6:00 pm followed by bed at 8:00 pm. Compulsory Bible readings begin and end each day. Inmates do not work on Sundays, so they remain locked up except for religious services. Staffing is usually low; fewer than a dozen staff—including a part-time Church of England chaplain—might work in an establishment catering to hundreds of inmates; workhouses must keep costs down. Discipline is harsh. Staff may restrict or withhold food for swearing or feigning sickness, and they may administer beatings with a rod to men and women alike for disorderly conduct. Many workhouses have at least one cell for solitary confinement where a person can find themselves locked up for the most minor of infractions. If the workhouses’ own deterrents are not enough, the habitually wayward inmate (one who refuses to work after receiving food, for example, or one who vandalizes workhouse property) can end up inside a prison.

Since the overall aim is to get the able-bodied off parish relief, the workhouse looks for outside employment for capable inmates—usually domestic service for women and labouring jobs for men. Children may be apprenticed to tradesmen or the factories, or sent into domestic service, by workhouse officials, without parental permission or knowledge; they are bound to that apprenticeship until they turn 21.

The workhouse can serve as an asylum for “harmless lunatics” when no other care is readily available, although in larger cities like London, purpose-built asylums cater to such folk (see Asylums, page 33). Workhouse conditions do improve over the Gaslight era, especially regarding medical care and food quality. By the end of the century, the workhouse population is largely elderly; only about 20 percent of those admitted to workhouses are unemployed or destitute, but about 30 percent of the population over 70 are in workhouses.

The ultimate humiliation, from a Victorian perspective, is the prospect of being anatomized. The Anatomy Act of 1832 permits anyone “having lawful Possession of the Body of any deceased Person” to sell that body to a medical school, and the Sanitary Act of 1866 gives lawful possession to the poor law union relieving officer, if a body in a mortuary is not claimed within 48 hours or buried within a period set locally by the authorities.

Keeper Note: workhouse records are extensive and may provide clues to investigators.

Floorplans

The following floorplans show a range of typical homes and may provide information or serve as potential locations for scenarios.

Rookeries

The slums are not mapped. Rookeries were (and should be) unmappable—they are three dimensional labyrinths where no floor matches the one below or above; clusters of jerry-built extensions, corridors, tunnels, divided rooms, sub-basements, courtyards, lean-tos, workshops, and kitchens. Investigators from the outside world should get lost, every time, unless they manage a successful Navigation roll.

The most striking feature to investigators venturing within should be the overcrowding, particularly after nightfall when workers come home. Homelessness is endemic and people sleep anywhere they can. Ten unrelated people living in the same room is perfectly common, most of them young—the median age by 1901 is only 24. Mobs of children are everywhere.

A well-heeled middle-class investigator group should be constantly on-edge and feeling guilty when playing tourist in a rookery. They do not belong here, and everyone knows that. The atmosphere should be unwelcoming and tense, at least, and hostile at worst, though some inhabitants may display (or fake) fawning attention. When the investigators retreat or escape, there is an excellent chance they’ll bring some unwanted souvenir away—lice, fleas, bedbugs, scabies, human ordure on their shoes or clothes, some sort of infection, or a rat bite. Use Table 1: Rookery Encounters (page 20) for inspiration and improvised encounters.

Country House

London Town House

Middle-class Villa

Terraced Housing

Workhouse

Crime & Punishment

Victorian sentencing is notable in that the legal system does not treat crimes of violence (short of murder) as more egregious than crimes against property. Society treats violence among the working classes as an intractable moral failing, and it is common to receive only a few months’ imprisonment for beating someone to the verge of death. Notorious murderer Charles Peace (hanged 1879), had on a previous occasion nearly killed a policeman and received only a six-year sentence, whereas a burglary without violence earned him eight years “inside.”

Typical sentences for common crimes

- Attempted murder: from 12 months imprisonment to 8 years of hard labor.

- Petty theft (first offense): from a caution or small fine, up to 3 to 6 months imprisonment. Birching (boys only).

- Petty theft (repeat offenses): up to 10 years hard labor. Birching (boys only).

- Housebreaking, burglary, or robbery (first offense): from 6 months hard labor to 2 years imprisonment.

- Housebreaking, burglary, or robbery (repeat offenses): up to 10 years imprisonment.

- Fraud: up to 5 years hard labor.

- Assault (first offense): a fine of up to £5, or up to 3 months imprisonment.

- Assault (repeat offenses): up to 4 years hard labor.

- Grievous bodily harm (first offense): from 12 months imprisonment to 4 years hard labor.

- Grievous bodily harm (repeat offense): up to 7 years hard labor.

Penalties

In 1896, for every 1,000 guilty verdicts passed, an average of 516 result in imprisonment (of which 19 include penal servitude), 194 in fines, 120 are bound over on their own recognizances, and 34 are youths who are sent to industrial or reformatory schools.

Judges have tremendous discretion over the sentences handed down for non-capital crimes. In 1878, the Home Secretary becomes aware of “serious irregularities which pervade the whole system of sentences” that experts attribute to “the personal opinions of the judges.” Social class, character witnesses, personal circumstances, and genuine penitence can make a considerable difference to the sentence handed down. First offenders are often treated leniently to get them to reform through mercy—although not always; in one instance, a man receives a sentence of seven years hard labor for stealing a hen. Repeat offenders are more likely to have the book thrown at them.

Due to Victorian attitudes about the higher nature of the female character, crimes against women almost always receive a harsher sentence than equivalent offenses committed against a man, while a woman can usually expect a lighter sentence than a man for committing the same offense. The exceptions to this are women poisoners (Victorian society is paranoid about the possibility of women poisoning their husbands) and child-murderers (who shatter the myth of maternal purity). In addition, domestic violence is widespread and rarely punished, not least because the prosecution must be brought by the injured party; though it is commonplace for working-class women to initiate prosecutions against their abusive husbands simply to shame them into better behaviour, not with any desire or expectation of having them locked up—an imprisoned man can’t pay rent, after all.

Juveniles, tried in adult courts, spend their sentences in adult jails throughout the 19th century.

Fines

Courts relatively rarely levy fines, as most criminals are not able to afford them. Magistrates and judges may impose fines if they think the criminal has the wherewithal to pay and will do so promptly.

Getting away with it

Even if investigators fall into the hands of the forces of law, there is a better than average chance they can escape legal punishment to battle the Mythos another day—if that is the Keeper’s preference. At the end of the 19th century, as many as half of all legal cases collapse before the courts reach a verdict. There is no Director of Public Prosecutions until 1880, and, even then, he does little. Justices of the Peace and other officials may prosecute “on indictment” by the coroner’s jury if there is a body, and the police may bring prosecutions if they catch a thief, but most crimes—even murder cases—are usually “by appeal” of an interested party such as a victim’s relative. Many public prosecution cases are prepared by the police who, lacking resources, time, or formal legal training, make mistakes and leave loopholes for lawyers to exploit. In minor cases, at the Keeper’s discretion, a simple Law or even Luck roll will suffice to see if a prosecution collapses before the verdict. Failing that, the judge may simply be inclined to bind the malefactor over on their own recognizance. This is a double-edged sword: what applies to investigators applies to villains too.

Flogging & Birching

Only a judge can pass this sentence, not a magistrate. A law passed in 1820 prohibits the flogging of women and girls. Always combined for adult men with a term of imprisonment, flogging is with either a cat o’ nine tails or the birch rod—the judge specifies which and how many strokes. The law also prevents use of the “cat” on boys under 16, but not the birch. Flogging is only for crimes of robbery with violence, vagrancy, and crimes of vice, such as importuning a minor and pimping, and for the punishment of those already incarcerated, if they break prison rules.

Authorities consider birching a particularly suitable punishment for boys aged 14 or under (16 or under in Scotland), as they view it as a relatively minor punishment and more humane than imprisonment; it’s almost always ordered as a punishment for petty theft. The birch used is smaller and lighter than the ones used on adult men in prison. After 1879, it takes the form of an immediate birching by a policeman, to a maximum of 12 strokes, in the nearest police station or sometimes in the court building itself.

Hard labour

Also known as penal servitude. Any lengthy prison term may include at least a period of hard labour. By the Prison Act (1865), every male prisoner over 16 sentenced to a “term with hard labour” must spend at least three months of his sentence in this way. Examples of such labour include rock-breaking or road-building on a chain gang, oakum-picking (untwisting old ropes), mailbag sewing, or netmaking. The work is intentionally tiring and monotonous—the better to teach inmates the error of their ways and break their will. Some prisons have workshops where inmates make useful items such as shoes and furniture. Where meaningful labour is not available, futile labour is the substitute.

The penal treadmill is a rotating, stepped device that prisoners must climb. A stint on the treadmill consists of 15 minutes climbing, followed by five minutes rest, for six hours a day. It may power prison machinery, such as a pump or a flour mill, or the energy may simply go to waste (known as “grinding the wind”). Alternatively, the crank machine consists of a small wheel, like the wheel of a paddle steamer, and a handle, which, turned by the prisoner, makes it revolve in a box partially filled with sand. A counter on the crank ensures that the prisoner works hard enough to “earn” his meals. By 1895, use of these devices is falling off; there are only 39 treadmills and 29 cranks in use in English prisons, and legislation abolishes them entirely soon after the turn of the century.

Life Sentences

It is important to note that in Britain, even in the 19th century, a “life sentence” does not mean “the rest of your life.” Generally, it means not less than seven years, and is usually a decade or so. The actual length of time served depends on the attitude of the prisoner—are they cooperative, non-violent, and humble? Do they appear to have seen the error of their ways? Do they still represent a threat to law and order? Also considered is the level of public interest in their release.

Campaigns by high-profile figures, influential persons, the press, or large numbers of the public, can shorten sentences considerably. It is quite unusual for “Lifers” to die of old age inside prison; they almost always end up out “on License” once they start to become decrepit—typically, they end up in the workhouse at this point. From 1877, such decisions rest with the Prison Commission, and may be directed by the Home Secretary, who also recommends the appointment, by royal warrant, of the Commissioners.

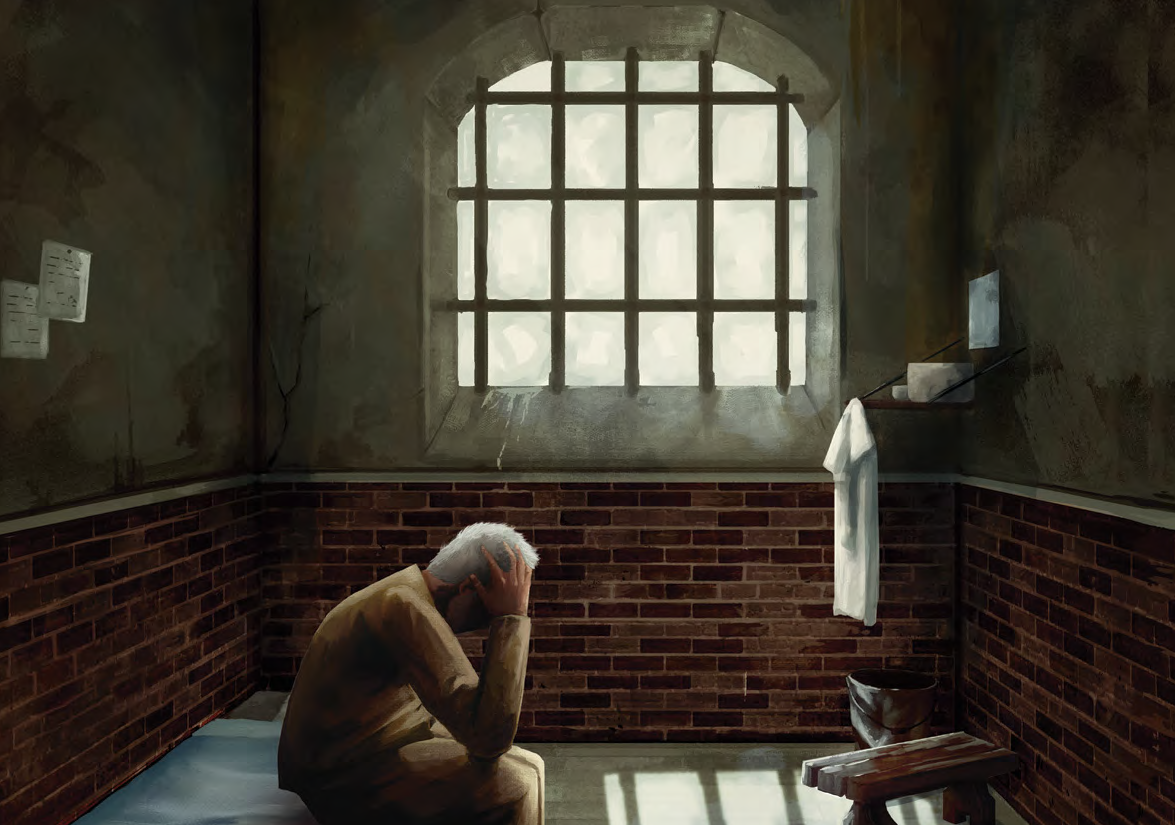

Prisons

By the latter part of the 19th century, prison reformers have ensured that life in prison is no longer quite the miserable hellhole it once was, with with unlit common rooms where prisoners of every type were crammed together. The ending of transportation to the colonies in 1868 means that many new prisons appear out of necessity—90 of them by 1870. In general, these now allow light and space, and prisoners have their own cell with adequate sanitation facilities.

The prison diet is nutritious, if extremely monotonous—for some criminals, it might be the best meals they will ever eat. Prisoners doing hard labour receive an adequate diet to ensure they are fit enough to carry out their sentence. Incarceration’s objective is to perform both a deterrent and reforming effect; strict discipline without undue pain is the intention. Each cell in Milburn Prison has a single window that emits light from a central courtyard, and holds a washing tub, a wooden stool, a bed, and several “improving books,” including a Bible, a prayer book, a hymn-book, and an arithmetic book.

The reality is, of course, much harsher than the stated intention. “Hard labour, hard fare, and a hard bed” is the overall culture. After 1865, all prisons run what authorities call the “separate system” where jailers actively prevent prisoners from interacting with each other. The intention is twofold: first, to prevent the development of conspiracies, partnerships, and the acquisition of criminal skills; and second, a belief that long periods of silent contemplation with only a Bible for company can awaken the “small quiet voice” of the conscience, resulting in inmates renouncing their life of crime and becoming contributing members of society.

Inmates in the separate system spend the first nine months of their sentence in solitary confinement before being allowed to join the main prison population. Even here, their interactions are severely limited, as during exercise periods (usually one hour per day) many prisons require inmates to wear masks that allow them to see only their feet and their food. Work takes place in the prisoner’s cell. Church services (essential for the moral development of the criminal) are mandatory; to prevent prisoners communicating, prison chapels have individual pews surrounded on three sides, forcing the members of the congregation to look at the pulpit.

Under the less staff-intensive “silent system,” more face-to-face contact might occur during communal labour and dining, and even shared accommodation, but regulations strictly forbid prisoners from speaking at all. If discovered communicating in any way, inmates face severe punishment, including a bread-and-water diet, a return to solitary confinement, and flogging. Prisoners develop means of communicating, including singing their conversations during hymns (surrounding inmates sing louder to cover up the conversation from the warders), lip reading, sign language, and slipping notes between cracks in bricks and woodwork.

The degree of severity with which jailers enforce these regulations varies from prison to prison. Most harsh is Pentonville Prison, an institution feared by many, while in other places discipline is relatively lax. The system remains in force until the Gladstone Committee of 1894–5, which introduces more lenient conditions. The 1898 Prisons Act effectively abolishes the solitary system; the duration of solitary confinement is now a maximum of one month.

The psychological effects of long-term isolation in prison can be devastating. Suicide rates are high. Keepers may wish to impose a Sanity reduction (0/1D6 loss) on those imprisoned, to reflect the consequences of this “humane and improving regime.”

Famous Crimes

Here are some examples of late-Victorian crimes, which may spark inspiration for plots or serve as background for characters and scenarios.

Trial of the Detectives (1877)

Also known as the “Turf Fraud Scandal,” the Trial of the Detectives did much to undermine public trust in the still relatively new plainclothes detective branch of the police force. The case began with the arrest in Rotterdam in the Netherlands of Harry Benson and William Kurr, British confidence tricksters who had been running a fraudulent betting ring on English horse races across the continent, netting tens of thousands of pounds in the process.

When shipped back to London, the men revealed that they got away with it for so long because they were paying Metropolitan Police detectives to protect them. Three detectives: Detective Chief Inspectors Palmer and Druscovitch, and Detective Meiklejohn, received guilty verdicts for perverting the course of justice, while a fourth officer, Detective Chief Inspector Clarke, was acquitted but required to resign. As a result of this case, Scotland Yard reorganized police detectives into a dedicated unit in 1878—the Criminal Investigation Department, or CID.

The Barnes Mystery (1879)

This case, also known as the Richmond Murder, was notorious because it was a manifestation of a great middle-class fear: that house servants might turn violently upon their employers. On March 5, 1879, a box washed up near Barnes Railway Bridge containing a woman’s torso and legs, all wrapped in brown paper. A few days later, Kate Webster, the live-in maid of the widowed and somewhat eccentric Mrs. Julia Thomas, was seen by neighbours in Richmond trying to offload the house’s furniture to a Hammersmith publican (owner of a drinking house) while wearing her mistress’ clothes and using her name.

While Webster fled to her home in Ireland, the police searched the semi-detached house in Richmond and found fingerbones and bloodstains—and a letter with Webster’s home address. The head constable of Wexford, aware of Scotland Yard‘s interest in Webster, recognized her from a previous larceny arrest, and the Royal Irish Constabulary traced her to her Killanne and arrested her at her uncle’s farm. Crowds lined the streets in both Ireland and London to gawk and jeer her along her route. She tried unsuccessfully to blame the publican and two of her own friends for the murder, as well as pleading pregnancy, but was convicted at the Old Bailey and hanged—making a full confession before she died.

Webster had a long criminal history and a short, unsuccessful career as a maidservant. She’d quarrelled with Mrs. Thomas who’d given her a few days’ notice at the end of February, only a month after being engaged. She’d murdered her mistress by pushing her downstairs, dismembered the body, boiled it in the scullery copper, burned as much as she could, buried the head (which didn’t turn up until 2010), and dropped the rest in the Thames. She then spent three weeks living under Thomas’ identity—a further outrage to Victorian sensibilities—before anyone discovered her ruse. There were also claims that she offered the rendered fat to local people as beef dripping. The crime inspired multiple street ballads. The semi-detached murder house at 2 Mayfield Cottages, shut up for 20 years, was unsaleable and acquired a reputation for being haunted; it was the subject of several paranormal vigils.

The Resurrected Earl (1881)

Alexander Lindsay, 25th Earl of Crawford

Alexander Lindsay, 25th Earl of Crawford

Alexander Lindsay, 25th Earl of Crawford, died in Florence, Italy, in December 1880 and was brought home for burial in his family crypt at Dunecht House, Aberdeen (Scotland). For additional security, the family placed the corpse in a triple coffin—the inner of wood, the middle of lead, and the outer coffin of oak—and deposited it within a crypt covered by four slabs of granite and heaped over with planted up earth.

In late 1881, the family solicitor received an anonymous letter saying: “The remains of the late Earl of Crawford are not beneath the chapel [sic] at Dunecht as you believe, but were removed hence last spring, and the smell of decayed flowers ascending from the vault since that time will, on investigation, be found to proceed from another cause than flowers.” There was, naturally, a press sensation.

A search revealed that the late earl was missing although nothing else was—even the silver coffin fittings. The family organized a search and offered a £600 reward. Then 14 months after the first burial, the writer of the note, Charles Souter, was arrested and convicted of grave-robbing and sentenced to five years with hard labour; he was able to pinpoint the earl’s shallow grave a few hundred yards away. This time, the family buried the earl in a different family vault in Wigan, England.

Although many now attribute the motive for the grave-robbing to resurrectionists, this does not stand up to scrutiny. The body was unusually difficult to access, almost certainly already rotten by the time of the crime, and worthless anyway since the Anatomy Act of 1832 had made medical access to corpses much easier. Why target an aristocrat, whose family would engage the police, and why send a letter telling them? The motive was almost certainly vengeance with a side order of extortion. Lindsay had previously employed Souter as a rat-catcher, but he was dismissed for poaching on the estate.

The London Disappearances (1881-1890)

Also known as the West Ham Vanishings, this series of crimes targeted girls in West Ham, London—to the north and east of the city.

- Mary Seward, April 14, 1881.

- Eliza Carter, January 13, 1882.

- Clara Sutton, January 14, 1883.

- Amelia Jeffs, January 15, 1890.

All disappeared from West Road on the Portway; the area was respectable but poor—mostly dockworkers—and the assumption with both Seward and Carter was that a pair of “white slavers” (sex traffickers) who were rumored to be operating in the area lured the girls away to Belgium. There was considerable public and press interest. Police dragged the local ponds and searched empty properties, in vain. Even the offer of substantial cash rewards produced no results. Then the body of a girl was discovered in a wooden starch box that had been left with a Goswell Road carrier company with a false delivery address in January 1883—authorities tentatively identified it as neither of the missing girls but as Clara Sutton, a friend of Mary Seward’s who vanished from a position in service.

Nine years after the first Vanishing, a fourth child disappeared from West Road, and this time when the police (after two weeks) searched empty properties nearby, they found the body of Amelia Jeffs stashed in a cupboard of an empty house at 126 Portway. The police strongly suspected Joseph Roberts, the builder of the house, and his father, the watchman, who both claimed they had lost the keys; no charges were brought however, due to lack of evidence.

Keeper note: if a 14-year-old vanishes from home, the police will generally take prompt action, provided that the parents kick up enough fuss. They will almost certainly not investigate the disappearance a 14-yearold living away from home as a maid, except under pressure from the press or a magistrate or similar. Running away from a job in service is simply too common, and a 14-year-old working-class girl will not be regarded as a child but as a “flighty” young woman. This procedural police gap provides an opportunity for investigators to get involved in cases.

The Ripper Murders (1888)

Detective Inspector Frederick Abberline

Detective Inspector Frederick Abberline

The death of Mary Anne Nichols on Friday, August 31, 1888, and the four that followed it, sparked an unprecedented media frenzy, and created a myth that endures to this day. They were by no means the first or last killings in the East End, but a combination of police secrecy concerning the investigation, a moral panic over the lives of slum-dwellers (and an actual panic among those living in the areas at risk), the lack of closure, and the public’s taste for horror and sensationalism made the crimes nationally—and then globally—famous. It is an interesting debate as to why the Ripper is of such universal renown, even a century and a half later, and much might be made of the salacious focus on sex-work in movies and television, and the rise of 1970s conspiracy theories.

The murders all took place around the junction of Whitechapel Road and Commercial Street, though they fell into various police jurisdictions.

Initially, the investigations took place at the various Met divisions where the individual murders took place (the Assistant Chief Commissioner, Robert Anderson, was on convalescent leave for most of the investigation). After the murder of Nichols, Detective Inspectors Frederick Abberline and Walter Andrews from CID Central Office at Scotland Yard joined the investigation to provide additional assistance. The City of London Police became involved under Detective Inspector James McWilliam after the Eddowes murder, which occurred within the limits of the City of London. From September 1st, overall control of the investigation passed to Chief Inspector Donald Swanson of the CID. The Home Secretary at the time was Henry Matthews.

The Metropolitan Police was tight-lipped over the crimes, creating a story-hungry press who, for want of facts, published sensational accounts full of wild speculation. Such accounts led to the police and press receiving thousands of letters about the case, some from members of the public offering help; however, nearly 600 claimed to be from the killer, which helped not at all. “Leather Apron,” the “Red Fiend,” and “Saucy Jack” were names given to the killer, but the moniker of “Jack the Ripper” is the one that stuck, based on a letter received on September 25th at the Central News Agency (which was almost certainly a fake by one of the journalists).

The crimes entered the public consciousness and created a popular panic, in some cases far from the scene. As far north as Cumbria, reports spread of people fitting metal grilles to doors and windows to prevent anyone breaking in and murdering them. Further afield still, Glasgow police received letters claiming to be from the Ripper who would be “paying their city a call,” and, in a Welsh village, Miriam Howells dubbed herself the “Ripper of Penrhiwceiber” and sent threatening letters to her neighbors “for a lark.” They let her off with a severe warning.

In London, public anger at perceived police incompetence (though they had interviewed more than 2,000 people, investigated “upwards of 300,” and detained 80 by the end of October) forced the resignation of Sir Charles Warren, the highly unpopular Met Police Commissioner, on November 8th. Over the years, many speculated about potential suspects for the killings, but no arrests ever occurred. Some police thought more killings were the work of the Ripper, while others thought that not all the famous victims were the work of the same person, but rather copycats inspired by the press. Eventually, the furor died down, but the crimes left a legacy—not just as history’s most famous uncaught serial killer, but also drawing attention to life in the slums as never before, inspiring a wave of charitable activity and slum clearance.

Criminologists and writers made many speculations as to the Ripper‘s identity over the last 120 years, and named hundreds of suspects. Following is a list of some of the more notable doors where theorists placed blame:

- Dr. William Withey Gull, Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria.

- Prince Albert Victor (“Prince Eddy”), grandson of the queen.

- Montague John Druitt, barrister.

- Aaron Kosminski, a Polish Jew hairdresser, the suspect favored by Anderson.

- Michael Ostrog, a Russian confidence trickster with a history of incarceration in asylums.

- Walter Sickert, an artist slumming it in the East End.

- John Pizer, a Polish Jew boot-finisher, sometimes called “Leather Apron.”

- James Kelly, a murderer who’d escaped Broadmoor in early 1888.

- Francis R. Tumblety, an American “quack” doctor visiting London at the time.

- Robert D’Onston Stephenson, a soldier, occultist, and journalist, who publicly speculated that the Ripper murders were a black-magic ritual.

- James Maybrick, a Liverpool cotton merchant, body wrecked by an addiction to arsenic.

- Severin Klosowski (a.k.a. George Chapman), a Polish hairdresser who poisoned his wives.

- Mary Pearcey (“Jill the Ripper”), a murderous midwife.

Keepers interested in making use of the Jack the Ripper case in their games might find that their players are already too familiar with some of the events and theories, but it might nevertheless serve as an intense investigation, with some work. On more than one occasion, a victim surfaced so quickly that the Ripper must have been in the immediate vicinity, yet still escaped unseen. They must have had an ability to blend into the Whitechapel surroundings and known their way about extremely well.

The Murders Experts generally regard the following five murders as canonical Ripper victims:

- Mary Ann Nichols “Polly,” murdered Friday, August 31st, 1888, on Buck’s Row.

- Annie Chapman “Dark Annie,” murdered Saturday, September 8th, 1888, on Hanbury Street.

- Elizabeth Stride “Long Liz,” murdered Sunday, September 30th, 1888, in Dutfield’s Yard.

- Catherine Eddowes “Kate Kelly,” also murdered September 30th in Mitre Square.

- Mary Jane Kelly “Marie Jeanette,” murdered Friday, November 9th, 1888, in her lodgings at Miller’s Court.

There are compelling arguments that the death of Martha Tabram on Tuesday, August 7th, 1888, was the first in the series, and there may have been others afterward. Whitechapel was the scene of several other unsolved murders during that period, such as the Pinchin Street Torso in September 1889, that were not Ripper cases.

The victims were all part-time Whitechapel sex workers, living hand-to-mouth; all went by numerous aliases throughout chaotic lives, and all had alcohol problems—as was extremely common in that area of London. Except for the last victim, they were all found outdoors, in alleys and courtyards. Strangled unconscious, a cut to the throat killed them before their mutilation. Parts of the bodies were missing, taken away by the killer. The nature of the mutilations indicated a sexual motive, but there was no evidence of rape.

On the night of September 30th, the authorities discovered unusual graffiti chalked on a wall in Goulston Street, not far from the scene of the Eddowes murder: “The Juwes are the men That Will not be Blamed for nothing.” Some attribute a Masonic meaning to this message, but its true import and author have never come to light. A portion of Catherine Eddowes’ bloodsoaked apron was in a doorway near the graffiti. The police had the graffiti removed before anyone could photograph it, for fear of it sparking antisemitic riots in the East End.

On October 16th, George Lusk, the president of volunteer group the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, received half a human kidney in the mail. A note accompanying the organ—addressed “From Hell”—alleged that the sender fried and ate the other half. The letter also claimed that the kidney was that of Catharine Eddowes; some experts dispute this. This is the only “letter from the Ripper“ ever seriously considered authentic by criminologists. Police interviewed numerous suspects and alleged witnesses to the Ripper crimes, police and the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee patrolled the streets of Whitechapel, and psychic Robert James Lees claimed to have had visions of the killer, but in the end, the identity of Jack the Ripper never came to light. In 1892, Scotland Yard closed the file on the Ripper, sealing it away from the general public for 100 years.

The Lambeth Poisoner (1892)

Dr. Thomas Neill Cream was a serial killer specializing in the use of chloroform and strychnine, and a determined but incompetent blackmailer. Glasgowborn but raised in Canada, he fled to America after the suspicious deaths of both his wife and mistress. In Chicago, he became an illegal (and sometimes lethal) abortionist, then received a life sentence for the poisoning of his lover’s husband—and attempting to blackmail the pharmacist involved. He walked out a free man after 10 years (and a brother’s hefty bribe to the Governor for clemency).

Returning to Britain in late 1891 and settling in London, Dr. Cream began a pattern of murder. He would buy drinks for sex workers, slip strychnine pills into the cup or bottle, then, when his victim died, would write to some prominent gentleman (doctors or prominent tradesmen) blaming them and demanding large sums of cash. He’d also send anonymous tip-offs to the police. These blackmail attempts don’t ever seem to have been successful, but they roused the suspicions of the police as the writer clearly knew too much.

Dr. Cream rashly made no attempt to disassociate himself from the scenes of the crimes, even going so far as to give a visiting American policeman a tour. In June 1892, Dr. Cream was arrested and charged with the murders of Ellen Donworth, Louise Harvey, Alice Marsh, and Emma Shrivell, along with one more attempted poisoning, and extortion. He was hanged after the jury took a mere 12 minutes to convict him.

The Ogress of Reading (1896)

Amelia Dyer

Amelia Dyer

Amelia Dyer was arrested on April 4th, 1896, on suspicion of murder. Police became aware of Dyer when they discovered of a body of a baby girl in the River Thames, wrapped in papers bearing Dyer’s address. When the police entered Dyer’s house in Reading (pronounced “Redding”), the unmistakable stink of rotting flesh was present, as well as dozens of adoption papers, letters from concerned mothers, child-sized sets of clothes, and pawnbrokers’ slips for yet more.

In an era when illegitimate and unwanted babies were rife, it was common practice to turn them over to old women who would care for them for a weekly fee, or promise to adopt them out. Unregulated fosterers, known colloquially as “baby farmers,” often deliberately allowed their charges to waste slowly to death—sedated with Godfrey’s Cordial or some similar opiate if the infants were lucky. Dyer had turned “baby farming” into an industry. Charging a fee of £10 to adopt out an unwanted child, she had been taking children in for at least ten years. Neighbours reported as many as six children a day entering her house. A police investigation indicated that she had taken in at least 20 infants in the two months preceding her arrest. None of the children entrusted to her care survived.

Dragging the Thames near Dyer’s house turned up more than 40 bodies and skeletons, most of them under one year old and many with a white ribbon around their neck—Dyer’s preferred manner of strangulation. It is unknown how many children Dyer murdered, but modern estimates suggest that in her years of business, she may have killed 300–400+ victims, making her one of the most prolific serial killers the world has ever known.

After her arrest, Dyer became a household name. It took a jury less than five minutes to find her guilty and she was hanged on June 10, 1896.

The Forty Elephants (1873-1950s)

An all-male gang of criminals known as “The Elephant and Castle Gang“ operated on a semi-professional basis out of the Elephant and Castle area of London (itself named after a famous pub), and from them developed their female counterparts, the Forty Thieves, also known as the “Forty Elephants.”

Although uncertain, it is probable that the Forty Elephants developed from several factors, including wives and girlfriends of career criminals (several of the gang’s members were supporting men who were in prison for their crimes), women preferring the profits of crime to a life of poverty, and the need for mutual support. The group is first mentioned in the newspapers in 1873, but it is likely they had existed in some form for years before that—police reports from earlier in the century suggest they had known of an organized group of female shoplifters working the area for decades.

The Forty Elephants specialized in pickpocketing, blackmail, and shoplifting (the considerable volume of Victorian ladies’ underclothes providing ample hiding places for stolen goods, especially after the addition of extra hidden pockets). Gang members would pose as servants in wealthy households and open the doors to allow the place to be cleaned out. They would enter affairs with respectable men and then blackmail them with threats of revealing all.

The gang targeted expensive West End stores for their thefts, “putting on the posh” to blend in with customers as they helped themselves to jewelry, furs, and silks. Eventually, the gang’s members became so well-known to shopkeepers that they would raise an alert if the gang was working in the vicinity—this led to the Forty Elephants expanding their reach through rail links to other towns and seaside resorts outside of London.

The gang was territorial and loyal to one another. They were quite prepared to dish out punishment with metal bars or knives to enemies. They expected other criminals on their turf to pay a commission on any proceeds, and when one of their number went to jail, the gang would pay for the finest defense they could afford. The Forty Elephants were successful enough to survive into the middle of the 20th century, using a cell structure to prevent individual arrests bringing the entire gang down. A reporter once described them as running “the largest organized shoplifting operation ever seen in Britain.”

Queen of the Forty Elephant

Mary Carr, a.k.a. Polly Carr, a.k.a. Mary Crane, a.k.a. Jenny Lesley, a.k.a. “Swan-neck” was leader of the Forty Elephants criminal gang.

Little is known for certain about Mary Carr—if that was even her real name. As late as 1900, she was giving her age as 29, but records show that she was born on Smith Street, Westminster in 1864. Carr first appears in court records at the age of 12 in 1876 for petty theft, when she is let off with a caution. From there, she became a flower-seller on the Strand.

Carr was undoubtedly a woman of striking looks, quick wits, and charisma. As well as selling flowers, she appears to have worked as an artist’s model at times (including for society painter Lord Leighton), and, by the 1880s, she had risen to become the leader of the Forty Elephants, gathering an obedient gang of female criminals around her.

In 1896, she received a sentence of three years of penal servitude for the kidnapping of a child from Epsom Racecourse. She was back in court in 1899 for theft, for which she received a sentence of four months hard labor, and again in 1900 with a man named Charles Harvey when the pair went to prison for robbing rooms in West End hotels.

Court reports from 1896 describe Carr as having golden hair and being “…dressed magnificently. She wore a rich black mantle, heavily trimmed with fur, over a splendid silk dress, whilst on her head she wore a broad Rembrandt hat trimmed with five ostrich feathers… the possessor of an exceptionally fine figure (who) carries her head in a stately manner.” She wore large diamond rings that were not only of considerable value but also lent weight to her punch. History is vague on what became of Carr, although the Forty Elephants rose to even greater heights of infamy when Alice Black, a.k.a. Alice Diamond, succeeded her as leader of the Forty Elephants in 1915.

The Napoleon of Crime (1873+)

Adam Worth was the greatest, most successful crime lord of Victorian London. Born in Germany in 1844, Worth’s family moved to the United States when he was five. He ran away from home at 14, and at 17, joined the Union Army to fight in the American Civil War. At the battle of Bull Run, Sergeant Worth had his first taste of the horrors of war and decided it wasn’t for him, so he faked his own death and deserted. Moving to New York, he took to a life of crime, starting with pickpocketing before graduating to safecracking and bank robbery. In 1869, hotly pursued by the law after one bank job too many, he and an accomplice—“Piano” Charley Bullard—left for Europe.

Pausing in Liverpool just long enough to rob the place blind and pick up a shared girlfriend, Worth and Bullard arrived in Paris, where they founded the American Club—a high-class restaurant, cocktail bar, and illegal gambling den. The enterprise soon became the centre for a rapidly expanding crime network run by Worth; however, these activities drew the attention of the French police and the Pinkertons, so Worth and Bullard left for London in 1873. Taking an apartment in Piccadilly and a mansion in Clapham Common, Worth spent the next two decades building a criminal empire of global reach.

Worth realized that the risk of crime often outweighed the rewards, so he built a network for which he did the planning but took few personal risks. In their files, the Pinkertons said: “for years he perpetrated every form of theft—forging, swindling, larceny, safe-cracking, diamond robbery, mail robbery, burglary… hold-ups and bank robbery… In the latter 70s and all through the 80s one big robbery followed another. The fine hand of Adam Worth could be traced, but not proven, to almost every one of them.”

Over his career, Worth and his network stole an estimated three million pounds (equivalent to at least a hundred times that amount today). His greatest crime was the theft in 1876 of Gainsborough’s portrait, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, the most famous and expensive picture in the world at the time. Worth liked the painting so much that he kept it.

Worth was an unusual man. He refused to engage in violent crime and would not work with violent criminals. Members of his gang who landed themselves in trouble would receive money or the best legal help money could buy. Worth could fit in anywhere and acted the gentleman. He was kind, generous, respectful to women, and would only steal from those he felt could afford it. At the same time, he was a relentless thief who stole without compunction, and this was ultimately his undoing. In Brussels in 1892, he robbed a mail coach on a whim and was caught, identified, and sent to prison until his release in 1897.

Thereafter, his criminal career tapered off, committing just one jewellery shop robbery to cover living expenses. After returning the Gainsborough painting to the art dealer for $25,000, he came to an agreement with the Pinkerton’s Agency that involved dictating his full memoir. After this, he went into apparent retirement in London. He died in 1902 and now lies in a pauper’s grave in Highgate Cemetery, his huge fortune gone… somewhere. His son became a Pinkerton’s detective.

The Murder Castle

For those Keepers whose investigators venture abroad to the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, an encounter with Dr. H. H. Holmes (1861–1896) seems too good an opportunity to miss. Billed as “America’s First Modern Serial Killer,” Holmes did it with a truly gothic sense of drama. The facts have been somewhat mythologized over time—not least by Holmes himself, who “confessed” to the murders of 27 people, some of whom were still alive—but the myths make for irresistible gameplay. Keepers should be wary of forewarning players who know the name, so make use of one of Holmes’ many aliases, which included Herman Webster Mudgett (his birth name), Henry Mansfield Howard, Hiram S. Campbell, and Alexander Bond.

Henry Howard Holmes trained in anatomy at a prestigious New Hampshire college and started his career in crime early with insurance fraud, supplying bodies to life-insurance companies. He also married three times without divorcing his previous wives. By 1886, he was associated with the deaths or disappearances of a couple of boys. In that same year, he moved to Chicago, changed his name, and launched a successful career as a druggist. Purchasing an empty plot on the corner of Sixty-Third Street and Wallace Street, he began construction of a city block known locally as The Castle, that was to become known as the World’s Fair Hotel, and years later as the Murder Castle.

Three stories high, this construction was never properly finished as a hotel, though he did use parts of it for purposes both legitimate and nefarious. Holmes persistently failed to pay his construction bills. The first floor housed shops, the second was a labyrinthine series of apartments, and the unfinished third was supposed to be hotel rooms.

Some of the more outrageous (but completely usable in-game) claims made by tabloids of the day were that Holmes rigged the second-floor apartments as a series of murder chambers; soundproofed and outfitted with chutes, they would drop straight down to the cavernous basement where Holmes had a dissecting table, acid vats, quicklime, and a furnace to dispose of his victims’ bodies (he actually did sell prepared bones and skeletons to medical institutions). Some rooms had hinged walls and false partitions, some connected by secret passageways, and one was even airtight with a gas inlet.

He rented the murder apartments to many visitors over the years, and was especially busy during the six months of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Missing tourists were by no means a priority of the Chicago police. By the end of the World Fair, so many people were disappearing that private detectives and relatives were turning up to make enquiries. With creditors closing in on him, Holmes set fire to the top floor of the building (causing minimal damage) and then fled to Fort Worth when a suspicious insurance agent blocked his $6,000 claim and arrest seemed imminent.

The rest of his criminal history needs no mythologizing; it’s horrific as it stands. Holmes took a series of mistresses, most of whom ended up dead after transferring property to him. He killed his accomplice in crime and fraud, Benjamin Pitezel, to cash in on a $10,000 insurance policy, and transported Pitezel’s three children all the way to Toronto, murdering them and burying the bodies under rented houses.

His total number of victims is unknown; it may have been as high as 200. The Pinkertons finally arrested him in Boston in late 1894 on a horse theft warrant, and that is when some tabloids claimed the first bodies were found and the myth of the “Murder Hotel” was born. Claims that numerous human remains were recovered from the basement were made without evidence, but that didn’t stop the yellow press.

He was hanged on May 7, 1896, for the murder of Pitezel, having confessed all after the trial. He claimed that he could feel himself physically changing into a devil. After his death, some odd accidents happened to detectives and officials involved in his case—the chairman of the jury suffered a freak electrocution, for example, and, according to some sources, the priest who gave his last rites died of unknown causes. The Murder Castle burned, gutting the interior.

Keepers wanting to set a scenario in the Murder Castle, or during the Chicago World’s Fair, should check out The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson (2003).

Asylums

Asylums tended to fall structurally into one of three types: the “conglomerate,” a hodgepodge of miscellaneous structures, such as Suffolk Country Asylum; the “corridor,” with wards connected by corridors up to a quarter of a mile in length, such as Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum in Middlesex (it has the longest indoor corridor in Britain); and the “pavilion,” where rows of female and male blocks each house up to 200 patients, such as Leavesden Hospital in Hertfordshire.

Usually, an asylum resembles a large country house, often with a spacious landscaped garden of many acres. Some include farms and sports fields, as well as airing courts to allow patients to view the surrounding countryside (fresh air and exercise being an important part of treatment).

Of the major asylums, Bethlem is by far the worst for general maltreatment. Holloway Sanatorium is the asylum for Keepers who intend their investigators to have an easy chance of absconding; it is a philanthropic model of progressive care for harmless patients-a refuge for up to a year for middle-class people suffering from temporary breakdowns-with an experimental and open regime (inmates may even walk into the local village to shop). For the murderously insane, high-security incarceration is available from the penal system at Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, which has five blocks for male patients and one for female.

A patient’s standing, as either a pauper or private patient, determines their level of housing in a ward appropriate to their status. The wards of private patients have fewer beds and a degree of privacy, while pauper wards squeeze in as many beds as staff can fit. Usually, there is strict segregation by sex, with male and female wards housed in different wings or in separate buildings.

Asylum life is regimented, based on clear routines and orderliness, which is considered calming for the patients. Patients wake at 7:00 am for breakfast (tea, coffee, or cocoa, with porridge and bread), followed by a midday meal at 12:30 pm, and later, a tea (bread and cake) served in the early evening. Outside of meal times, routines often differ for men and women. A male patient might work on the asylum’s farm, in the bakery, or in a kitchen, while a female patient can expect to remain inside, working in a laundry, sewing in a “mending room,” or cleaning.

Those who can’t (or won’t) work might spend time in an outside airing court for an hour in the morning and afternoon, but otherwise remain confined to their ward. Difficult patients usually are subject to restraint, e.g., a straitjacket or tied to a bed. Restraint in a cell is only for the most troubling or aggressive patients.

As the new century approaches, new techniques and treatments came to the fore, as well as more benevolent caring practices, but such forward thinking varied greatly between institutions. It isn’t until the century that newer treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and lobotomy (removal of parts of the brain), begin to see use. Treatments like group therapy, anti-depressants, and anti-psychotics are not known until well into the mid century.

Note that a high proportion of those admitted to a Victorian asylum would be suffering from the psychosis and delirium of tertiary syphilis, for which no cure was available, and death was the only outcome.

Table 2: Asylums

| London Area | Location | Date Founded | Cure Rate | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bethlem Hospital | St George’s Fields, Southwark | 1247 | 20% | 300 |

| City of London Lunatic Asylum | Stone, nr. Dartford | 1866 | 30% | 470 |

| Claybury Lunatic Asylum | Woodford Bridge, Middlesex | 1893 | 40% | 2,500 |

| Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum | Friern Barnet (now Barnet) | 1851 | 25% | 2,500 |

| The Heath Asylum | Bexley | 1898 | 30% | 2,000 |

| North of England | Location | Date Founded | Cure Rate | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lancashire County Lunatic Asylum | Lancaster | 1816 | 30% | 2,100 |

| Liverpool Lunatic Asylum | Lime Street, Liverpool | 1792 | 20% | 70 |

| Manchester Royal Lunatic Asylum | Manchester | 1849 | 40% | 300 |

| North Riding Lunatic Asylum | Clifton, York | 1847 | 20% | 709 |

| Newcastle-upon-Tyne City Asylum | Gosforth, Newcastle | 1869 | 35% | 503 |

| The Friends’ Retreat | York | 1792 | 45% | 160 |

| Midlands and East of England | Location | Date Founded | Cure Rate | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buckinghamshire County Asylum | Stone, Aylesbury | 1853 | 40% | 480 |

| Holloway Sanatorium | Virginia Water, Surrey | 1885 | 50% | 410 |

| Leicester & Rutland Asylum | Victoria Road, Leicester | 1837 | 30 % | 480 |

| Lincolnshire County Asylum | Bracebridge, Lincoln | 1852 | 40% | 680 |

| Norwich Borough Asylum | Hellesdon, Norwich | 1880 | 30% | 315 |

| Nottingham Borough Lunatic Asylum | Mapperley Hill, Nottingham | 1880 | 30% | 585 |

| Oxford County Pauper Lunatic Asylum | Littlemore | 1846 | 40% | 553 |

| Royal Naval Hospital (inc. asylum from 1863) | Great Yarmouth, Norfolk | 1863 | 40% | 227 |

| Warwickshire County Pauper Lunatic Asylum | Hatton, Warwick | 1852 | 40% | 1,047 |

| South of England | Location | Date Founded | Cure Rate | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum | Crowthorne, Berkshire | 1863 | 20% | 665 |

| City of Exeter Lunatic Asylum | Exeter, Devon | 1886 | 40%. | 377 |

| Cornwall County Asylum | Bodmin, Cornwall | 1820 | 35% | 750 |

| Hampshire County Asylum | Knowle, Hampshire | 1852 | 30% | 1,061 |

| Kent County Asylum | Maidstone, Kent | 1833 | 40% | 1,577 |

| Plymouth Borough Asylum | Ivybridge, Devon | 1891 | 30% | 275 |

| Royal Military Lunatic Hospital | Netley, Hampshire | 1870 | 35% | 1,077 |

| Wales | Location | Date Founded | Cure Rate | Capacity |

| Joint Counties’ Lunatic Asylum | Abergavenny, South Wales | 1851 | 30% | 1,077 |

| North Wales Counties Lunatic Asylum | Denbigh, North Wales | 1848 | 40% | 1,500 |

| Scotland | Location | Date Founded | Cure Rate | Capacity |

| Aberdeen Royal Lunatic Asylum | Aberdeen | 1800 | 40% | 720 |

| The Crichton Royal Institution | Dumfries | 1840 | 45% | 800 |

| Edinburgh Royal Lunatic Asylum | Edinburgh | 1813 | 30% | 870 |

| Glasgow Royal Lunatic Asylum | Gartnavel | 1814 | 30% | 850 |

| Inverness District Asylum | Inverness | 1864 | 30% | 540 |

| Ireland | Location | Date Founded | Cure Rate | Capacity |

| Belfast District Asylum | Belfast | 1829 | 30% | 656 |

| Richmond District Asylum | Dublin | 1814 | 35% | 1,100 |

| Eglinton Lunatic Asylum | Cork | 1852 | 20% | 1,200 |

| Donegal District Lunatic Asylum | Letterkenny, nr. Donegal | 1866 | 30% | 300 |

| Cure rate: roll every month; success means 1D3 Sanity restored. If patient also makes a successful Sanity roll, underlying condition is cured. |

Water Therapy

Water was a popular way to treat a variety of conditions. Cold water, either in the form of a bath or shower, might be used to calm down aggressive or excitable patients, while soothing warm water, usually in a bath, was used for patients with melancholy. Patients received baths in specially designed devices, sometimes on a canvas hammock held in place by a metal frame and covered with warm or body temperature water up to their chin. Orderlies then covered the bath with a canvas sheet with a hole for the patient’s head, and they would stay there for hours, or sometimes days. Cold water drained at a controlled rate from the bottom of the bath, while warmer water replaced it.

Water was a popular way to treat a variety of conditions. Cold water, either in the form of a bath or shower, might be used to calm down aggressive or excitable patients, while soothing warm water, usually in a bath, was used for patients with melancholy. Patients received baths in specially designed devices, sometimes on a canvas hammock held in place by a metal frame and covered with warm or body temperature water up to their chin. Orderlies then covered the bath with a canvas sheet with a hole for the patient’s head, and they would stay there for hours, or sometimes days. Cold water drained at a controlled rate from the bottom of the bath, while warmer water replaced it.

Cold water therapy, on the other hand, could be extreme. In short, sharp bursts of 15 to 20 minutes, doctors prescribed it to soothe those in a highly excitable or manic state. Treatments varied by institution and doctor, but techniques included the following:

- Tying a patient to a chair and pouring buckets of cold water over their heads.

- Restraining a patient in a cold shower room and spraying water into their faces.

- Repeatedly using a chair to immerse a patient into a pool of water until they were at the point of unconsciousness before removing them from the water and allowing them to recover.

Villainous Organizations

There is plenty of scope for Keepers to create their own criminal gangs, Freemasonry lodges, and religious or occult societies to be sources of intrigue for investigators. The following organizations are ready-to-use examples for your convenience; feel free to tailor them as enemies, dubious allies, or scenario/campaign hooks-however you wish.

The Hatfield Club

Nominally a dining club for students at either Cambridge or Oxford University (Keeper’s choice). It is open by invitation only to wealthy upper-class males from aristocratic and royal families, and even by Oxbridge standards, it is elitist and expensive. Few students receive invitations-fewer than half a dozen a year-and they must prove their enthusiasm and loyalty through a series of humiliating initiation tests involving, among other things, a severed pig’s head.

When a new member is elected, the others trash his college room in the middle of the night. Members wear a special form of tailor-made dining dress when they meet, which harks back to the frock coats of the Regency Period when the club originated. They vie to host banquets for one another and like to dine in the most exclusive establishments, on the rarest viands, and consuming enormous amounts of vintage champagne and fine wine. Most crockery and crystalware ends up broken.

The Hatfield Club revels in oafish bad behavior, where members play arrogant japes that run the gamut from the tasteless to the cruel and criminalfor example, burning notes in front of poor people, smashing windows in the restaurant they have hired, or assaulting folk in railway carriages. If challenged, they often retaliate by “debagging” the waiter, train conductor, or policeman-that is, pulling their trousers down.

Whenever anything criminal is committed, they always extravagantly pay off the potential complainant on the spot, trusting to money to solve any and all problems. In the rare cases where people refuse to be bought off, familial connections of the club members make sure nothing comes to court and there are no repercussions; fathers or other Old Hatfield Boys cheerfully lean on police commissioners, the Masters of the University Colleges, business owners, and so on. Members of the Hatfield Club accept a night in jail as part of the fun, since they know they’ll be out in the morning, and they have therefore come to acquire the reputation of being untouchable.

Many members of the Hatfield Club go on to become members of the Lords and even Cabinet members. The Riot Club (2014) is a movie depiction of this kind of dining club.

Most Hatfield Club members grow out of their youthful exuberance as other societal pressures come to bear, but, for a few, the thrill of such excess without consequences becomes an irresistible addiction, and they plunge deeper into a defiance of moral and social strictures. For a core group of Old Hatfieldians, the party still goes on-only, now behind the high walls of private country estates. As powerful and influential men, it is easy for them to get away with far worse crimes than mere public debauchery.

Among these “entertainments” is the hunting of human beings with packs of foxhounds. The victims are usually poor and without connection, taken or lured from the streets of London where they will not be missed, and their abductors can’t be traced. A “Hatfield Hunt” takes place several times a year, on different landed estates around the country, and ends in the slaughter of a “vixen” (woman), “dog-fox” (man), or “brace” (mixed pair).

Naturally, trusted servants and some family members are aware of these goings on, but Old Hatfieldians are careful to compensate discretion and only target outsiders to their rural communities. Older members carefully vet and groom student members in their debauchery before admitting them to the murderous hunts; by the time they find out the worst, they have more than enough shameful secrets to be blackmailed into silence.

Possible Plot Connections

Mysterious disappearances in the East End; the discovery of a body torn apart by “wild animals” in the countryside; a thread in a folk-horror scenario; an upper-class investigator’s (or their friend’s) shameful past as a Hatfieldian that now becomes pressure to join in the hunt or to atone by bringing the Hatfield Club down.

The Morley Gang

The early decades of the century were a golden age for Britain’s ghouls. The swelling population of the towns, along with frequent outbreaks of cholera and smallpox, meant that churchyards of urban parishes became full to overflowing. Although their traditional territories were increasingly hemmed in by stone streets and the crammed dwellings of the living, there was so much ripe meat available that the ghoul population could boom. Straying and abandoned infants were plentiful and easily converted into new generations of scavengers.

The early decades of the century were a golden age for Britain’s ghouls. The swelling population of the towns, along with frequent outbreaks of cholera and smallpox, meant that churchyards of urban parishes became full to overflowing. Although their traditional territories were increasingly hemmed in by stone streets and the crammed dwellings of the living, there was so much ripe meat available that the ghoul population could boom. Straying and abandoned infants were plentiful and easily converted into new generations of scavengers.

Even though the Resurrection Men prowled the graveyards at night, searching for fresh corpses, there were enough to go around and, by and large, the living and the undead maintained an uneasy truce, with the ghouls having the distinct advantage of being able to tunnel unseen to their quarry.

Then came two blows to this unending feast and frolic. The 1832 Anatomy Act was a minor one (at least from the ghouls’ perspective), diverting more corpses from the burial grounds to the anatomical labs. But the mass closure of the parish churchyards on health grounds following the 1852 Burials Act was disastrous. One by one the ancient ghoul feasting grounds emptied, picked clean of their deposits. Although huge new cemeteries opened on the city fringes, they were miles from traditional territories and cut off by a hostile landscape full of the seething mass of humanity.

Ghouls, being naturally wary creatures in the face of superior human numbers and weaponry, and handicapped by not knowing where their food sources were now going, bickered fiercely among themselves; some urged a retreat to the Dreamlands, while others pushed for an aggressively proactive approach to acquiring dead bodies.

This is where the Morley family came in. They were based in the Devil’s Acre rookery near Westminster Abbey, London, and the Anatomy Act had dealt a withering blow to their lucrative family business as resurrectionists. As well as selling stolen bodies (for about 10 guineas each, but up to 20 guineas in a time of scarcity) they’d always made money on the side by selling off jewellery and clothes from the corpses they robbed.

When times grew hard, they tried to diversify into the undertaking business to continue their looting activities. Yet, this was risky-the Morleys could only harvest the rings and lockets from cadavers when collected from their homes, just before the coffin was nailed shut and practically under the noses of the bereaved-there was little profit to be made, anyway, from the paupers and lower-middle-class families that Morley and Sons had as clients. They craved a way of getting their hands upon the keepsakes of the extremely rich.

Mary Morley, matriarch of the family, made the bold decision in 1862 to strike up an alliance with the ghouls of London. It has been a remarkably long-lasting and successful partnership.

The first major act was to transport the bulk of the ghoul population, by night and in covered carts, out of the central metropolis to the new cemeteries that opened from the 1830s onward; the biggest ghoul populations are now in Kensal Green, Highgate, and Brompton. Further afield, there are large populations in Glasgow, in Sheffield General Cemetery, in Warstone Lane (Birmingham), in Philips Park (Manchester), and in other cities.

The ghouls play their part by extracting jewellery from coffins after burial and handing it over to the Morleys, who in turn lean hard on sextons, groundskeepers, and cemetery officials to turn a blind eye to the existence and activities of these necrophagous monsters, and make sure that the authorities never hear of it.

In recent years, the Morley Gang has expanded beyond its original family membership and far beyond London; they infiltrated and cowed undertakers’ businesses in every major city, keeping an eye on who is buried with what, so that the ghouls may effectively direct their efforts. It is thanks to pressure from the Morley Gang that the American fashion for embalming, which developed after their Civil War, never caught on with the British funeral industry, with bodies normally going into the ground as nature intended: edible.

The originators of this undertaking, Mary Morley and her three sons-Tom, Bert, and William-are still very much alive-though they have handed the reins of business on to succeeding generations, having less interest in money these days. They long ago succumbed to the temptations of eternal life as ghouls, and Mary, a corpulent, voracious eminence with a savage sense of humor, currently dwells in burrows below the Circle of Lebanon in Highgate Cemetery. Lesser officials in the gang are still human.

Possible Plot Connections

Coffins found to be empty during a legal disinterment; a race to lay claim to books, papers, or artifacts buried with an occultist; brutal killings by “wild animals” in or near cemeteries; passage through “the secret portal each tomb is known to have” into the Dreamlands; stories let slip by cemetery staff of strange nocturnal goings on; innocent undertakers asking for help against the “mob” who are taking over.

Pulp Cthulhu: The Galton Group

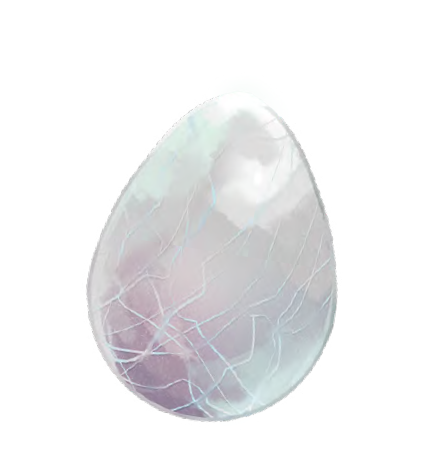

Founded by Francis Galton-Master Mason, Fellow of the Royal Society, medal winner of the Royal Geographical Society, explorer, and trailblazer in diverse fields including psychology, statistics, meteorology, and eugenics-this group consists of scientists and wealthy engineering eccentrics who aim to contact extra-terrestrial lifeforms and enable their forthcoming visit to Earth.

Galton (born 1822) was a child prodigy and widely regarded as a genius. While studying medicine at Trinity College, Cambridge, he suffered a nervous breakdown and was sent to recuperate in the Peak District of Derbyshire, where his family owned property including the Old Tor Mine, near the village of Castleton. While he was there, Galton interested himself in the mining of fluorspar Blue John, the rarest mineral in Britain. Miners presented him with an ovoid crystal that they recently found, and Galton later discovered that it sometimes fluoresced, and that gazing into it at these times gave rise to visions of starscapes and glimpses of distant worlds.

The crystal ovoid was, in fact, a communication device left behind by the mi-go during one of their prospecting visits. It allows the user to see across the vacuum of space. Galton found that it works best when a group concentrates together to guide its visionary “eye,” so he gathered a select number of people with astronomical and scientific expertise. This “Galton Group” decided to concentrate on the surface of the planet Mars: they saw red deserts, dried up canals, and crumbling ancient cities. More than that, they saw Martian life.

Plans to communicate with the Martians began immediately. The group assumed from the beginning that they would be, despite appearances, intellectually and morally equal or even superior to humans. A mirror and light array created on Rannoch Moor in Scotland allowed them to operate far from government interference. It proved successful. The Martians noticed the signals, built their own, and replied. From this breakthrough point in 1868, communication flowed back and forth, made considerably easier by the mi-go crystal. Ideas travelled from planet to planet between rational scientific minds, human and inhuman. Galton and his group, intoxicated by the thrill and pride of their discovery, completely overlooked the obvious dangers.

The Martians live on a depleted world. Their minerals, seas, and even their atmosphere, exhausted long ago by the mi-go’s strip mining, left only a fraction of the population that has mostly retreated underground. They practice a ruthless culling of weaker or unproductive individuals simply to stay alive; their “rational eugenics” inspire Galton to theorize publicly about its application on Earth, without him realizing (or, perhaps, caring) that it is a system born of crisis. The Martians can’t see Earth - they have no mi-go crystal-but they know now that it is rich in resources and ripe for conquest.

Most of the Galton Group are now well into a fanatical madness driven by repeated visions. They regard the Martians as a superior form of life, possessed of advanced scientific knowledge. They urge their Martian “friends” to descend to Earth and raise humanity to a new technological and social level, and the Martians are only too keen to oblige.

Blueprints, sent piecemeal from Mars, permit the construction of machines that allow soft Martian bodies to move about freely in Earth’s heavier gravity, and human engineers have set about secretly creating these, ready for the visitors’ arrival. On Mars, rockets are in full production. The Martians are coming. And the Galton Group will delight in selling out Earth.

The Galton Group are wealthy, elitist, and they possess technology far in advance of the Victorian norm, including heat-rays, robotic walking machines, and a telegeodynamic oscillator (an earthquake machine). When encountered, they believe they are working for the betterment of humankind, sort of-the mass of humanity is barely above the level of the dumb beasts, after all. It would not do to let a sentimental attachment to one’s own species get in the way of scientific and rational progress, would it?

Note: if desired, the Keeper can reframe this plot to avoid Martians by substituting the denizens of Mars with another Mythos race, which could even be the mi-go pretending to be the Martians.

The Crystal Egg (Mi-Go Artifact)

Usage Cost: 1 magic point per minute (groups may share this cost), and 1 Sanity point per viewing, per person.